Dr Thomas Sealey and Mr Simon Caxton talk us through their life changing case with IPS e.max ZirCAD Prime Esthetic:

Dr Thomas Sealey and Mr Simon Caxton talk us through their life changing case with IPS e.max ZirCAD Prime Esthetic. Read the full article below:

About the authors:

Dr. Thomas Sealey

Dr Thomas Sealey BChD, MMedEd, MSc Endo, is a multiple Award-winning cosmetic dentist and joint-owner of two private cosmetic dental practices where he lives in Essex, UK. Dr Sealey graduated from Leeds Dental University in 2006 and also holds an MSc in Endodontic Practice and a Masters degree in Medical Education. He is the co-inventor and co-owner of SmileFastTM and inventor of the Single-visit Orthodontic Lingual and Invisible Dual (SOLID) retention system. He has a special interest in achieving cosmetic smile makeovers using a minimally invasive approach and lectures on his techniques internationally. As one of only 19 dentists in the UK to hold the prestigious title of Full Accreditation with the British Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry, he has extensive experience in all aspects of dentistry, utilising orthodontics, advanced aesthetic composite restorations and ceramic smile design, to achieve perfectly natural smile transformations.

Mr. Simon Caxton

Simon Caxton co founded Simplee Dental Ceramics and has over 30 years' experience as a dental technician. He is a multiple award-winning technician and has won awards for his ceramic work from single restorations to full arch cosmetic cases. Simon has a keen interest in ceramics and has attended many courses across the UK and Europe from some of the world's most renowned technicians to broaden his knowledge and hone his skills as ceramist. Simon is a opinion leader for Ivoclar in the UK and uses his knowledge to teach other technicians the techniques he has learnt over the years. He has also lectured for Ivoclar on IPS e.max ZirCAD Prime and IPS e.max Prime Esthetic zirconia.

All the CAD designs for this case were done by Lee Wood who is also the co-founder of Simplee Dental Ceramics.

Tooth wear, or tooth surface loss (TSL), is a disease process that now affects a large proportion of the adult population. A degree of physiological tooth wear is expected throughout life and increasing age is a risk factor for increased severity of tooth wear. Recent literature present statistics indicating that the percentage of adults presenting with severe tooth wear increases from 3% at the age of 20 years to 17% at the age of 70 years[1]. An average reduction in crown length of 1.01mm for maxillary central incisors and 1.46mm for mandibular central incisors by a median age of 70 years can be expected through normal pathological wear processes[2]. Worldwide-reported prevalence of tooth wear varies considerably and has been quoted between 29–60% of the global population[3]. In total, 29% of Europeans are reported to have moderate tooth wear and 3% have severe wear, with the UK found to have the highest levels of tooth wear in Europe[4].

Numerous factors can contribute to higher incidence of tooth wear, but very often, tooth wear is multifactorial in nature, resulting from intrinsic acid, extrinsic acid, abrasion or attrition. Increasing levels of tooth wear are significantly associated with age[1] and diet[5]. Diagnosis and management of TSL can be complex and time-consuming, often requiring restoration of numerous teeth, with or without reorganisation of the occlusal scheme, as well as a multi-phase approach over a number of appointments, utilising potentially both direct and indirect methods of restoration.

Following a planning and restoration process utilising digital techniques and matrix delivery systems provides enhanced predictability when approaching these challenging TSL or full mouth rehabilitation cases. Digital techniques allow complete control by the clinician of the multiple variable factors that can compromise the success of these complex cases. The following case report demonstrates the workflow and successful outcome of using a digital planning and provision process, with the SmileFast Direct matrix delivery system, CFast digital orthodontics, and Ivoclar digitally produced final ceramic restorations.

Figure 1: Full smile – before

Figure 2: Frontal retracted view – before

This 58-year old female patient presented showing advanced tooth surface loss and loss of occlusal-vertical dimension (OVD) with passive overeruption of her anterior segment. She was struggling to enjoy the foods she loved and over the last few years had recoiled herself from any form of social engagement as she found public eating very difficult. She was very embarrassed of her smile and only smiled with her mouth closed. She had been in a profession with a lot of stress and had suffered in the past with gastric reflux. She also admitted to drinking 2 cans of carbonated soft drink every day for over 30 years.

After candid discussions it became very clear this lady’s objectives were to restore both function of her teeth and to restore her confidence, allowing her to once again enjoy social engagements and to eat and smile with friends and family. Her diet had changed dramatically as she had recently had two knee replacements and was on complex medication. She was no longer drinking the carbonated drinks.

Her main concern was the size discrepancies and tooth wear that was obvious within her smile. She had a low lip line and slightly deficient buccal corridors (Fig. 1). She was posturing into a pseudo-class 3 occlusion with passive overeruption of all her teeth, more noticeable on the anterior upper and lower labial segment (Fig. 2). She had missing posterior teeth and so all her mastication was on a reduced dental arch.

A full clinical examination and radiographic evaluation was completed. Every tooth was tested for vitality using heat and electric pulp tests. With the exception of the root-filled teeth and lower left second premolar tooth, the teeth were all stable and vital with good bone levels and periodontal support. Basic periodontal examination was completed and recorded as 1,1,2/-,1,-. There was no mobility to any teeth. There was severe tooth surface loss on the incisal/palatal aspects of every tooth. There were no soft tissue or hard tissue anomalies to report.

Panoramic radiograph (Fig. 3) showed radiolucency suggestive of chronic periapical pathology on both her upper right remaining molar teeth, her upper right canine tooth, and her lower left second premolar tooth. The root-treated upper right molar teeth were considered to be of a poor standard, with only partial obturation of the canals. Clinically there was an advanced area of dental decay undermining the distal aspect of the crown on the lower left second premolar tooth and caries noted on the upper right molar teeth.

Her teeth showed tooth surface loss and passive eruption of the both the upper and lower anterior segment with excessive upper gum on show during forced wide smiling. The diagnosis of severe attrition and tooth surface loss was made, as a result of previous acidic reflux, stress-related parafunction, and a highly acidic diet, which lead to the erosion and subsequent collapse of the arches and loss of occlusal-vertical dimension.

Figure 3: Panoramic radiograph

Figure 4: Digital mock-up for additive composite bonding

Figure 5: SmileFast stent placement

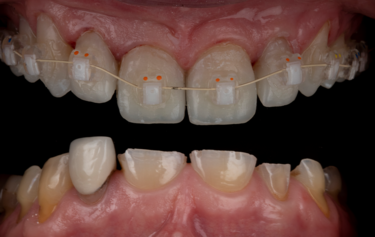

Figure 6: Direct comparison of digital mock-up and actual composite transfer

After full consultation and discussing all the options, costs, timeframes, on-going maintenance and repair costs, the patient proceeded to explore her options. A full set of clinical photos and digital intra-oral scan of her dentition was submitted to SmileFast where a digital mock-up for a restorative solution was returned (Fig. 4). Using the SmileFast integrated 3D software allowed her to visualise and understand the proposed option to correct and rebuild every tooth back to the correct proportions.

The upper teeth would ultimately require full-contour restorations to replace the lost palatal tooth surface and the lower teeth would require incisal addition to achieve the correct tooth-shape and proportions. This would result in an increase in OVD. The lack of posterior support was discussed and how the increase in OVD would result from the replacement of the lost tooth surface on the anterior teeth would change the patient’s bite relationship and return her into a Class 1 position. It was explained that treatment would proceed in a staged approach to allow the patient to accommodate and adjust to the new tooth and jaw relationships and to allow refinement of both tooth shapes and the OVD until she was functioning comfortably.

It was explained that using composite resin as an intermediate treatment stage would allow for the rebuild of her missing tooth structure. Once the tooth shapes were restored then fixed orthodontics could be used to correctly align the teeth and reverse the passive over-eruption of her anterior teeth, returning them back to their correct occlusal-vertical position. Further options to restore all her teeth with full coverage ceramic restorations to finalise the aesthetics and function of her new smile were also explored. The longevity and aesthetics of each type of restoration was explained, with both ceramic and composite options discussed.

All options were considered for the missing posterior teeth. Bone volume appeared favourable for the option of implant placement. The patient felt that she did not want to follow a surgical-restorative pathway at this time due to overall costs involved as well as the process itself for the replacement of the missing upper and lower molar teeth. Alternatives options were discussed.

Figure 7: Indirect orthodontic bracket bond-up stents in-situ

Figure 8: Immediate result after stent-guided composite build-up and orthodontic bracket placement

Figure 9: Tooth alignment after 5-months

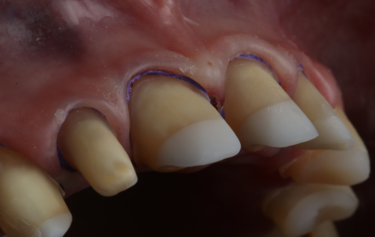

Figure 10: Digitally designed gingival recontouring guide

A putty trial stent was made on the 3D wax-up model of the proposed full-mouth rehabilitation mock-up and transferred over her teeth using a temporary crown and bridge bis-acryl material. This allowed the patient to visualise the smile enhancement and ensure she was happy and fully consented on the expected aesthetic result. This visual try-in is essential to stimulate and engage in conversations with patients to ensure complete understanding and robust consent is attained. In addition to ensuring the patient is fully agreed and consented to the planned clinical procedure, the trial appointment also allows the clinician to assess the teeth and smile for balance and function, better assessing how the restorations will affect the bite and guidance, which allows more diligent planning and opportunity for changes ahead of the final planned permanent restorations.

It was decided to remove the two molar teeth on the upper right and then to complete root canal treatment of the lower left premolar tooth, and a re-treatment of the upper right canine tooth. Direct composite veneer restorations would be placed using the digital SmileFast Direct stent to restore the size and proportions of all her remaining teeth, before fixed orthodontics would be used to re-align them. The final stage of treatment would be for provision of full-coverage ceramic restorations to restore the function and aesthetics of her teeth. All occlusal and potential parafunction influences were considered, as well as her complex medication and past dietary habits, and it was deemed that this approach would be the most favourable for this patient at this time and offer the highest success and longevity of her rehabilitated dentition.

The patient understood that there would be a substantial adjustment period to any of the treatment options we had discussed and that there would be the possibility of an evolving and adapting treatment plan in the following years. It was reiterated that we cannot predict future events and she must be aware that things may change in the future, and we will need to constantly evaluate her occlusal stability and remaining teeth and address any changes that are necessary at that time. It was explained that the success of rehabilitation would not only be due to the planning and clinical dentistry, but also due to her own determination and life-long commitment to maintenance of both the restorations and her oral health.

Figure 11: Measured depth-reduction grooves during tooth preparation

Figure 12: Provisional tooth preparations

Figure 13: Gingival retraction on final preparations

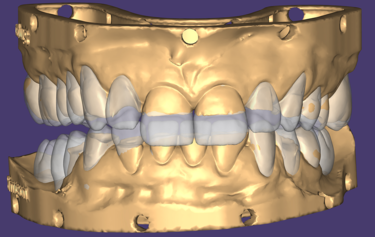

Figure 14: Final full mouth digital restoration designs

Matrix techniques are commonly used to transfer the shape and form of a planned new smile from a digital or analogue wax-up model to a patient’s teeth by using some form of stent and a suitable restorative medium, such as composite resin, to allow placement of provisional or even definitive restorations. There have been many variations on this technique, and all have inherent limitations and inadequacies. Often a flowable resin material is advocated for ease of placement and the idealised property of low-viscosity, but this comes at the sacrifice of mechanical strength and wear resistance. Many attempts have been made to improve the matrix transfer technique, but all have fallen short. In 2018 SmileFast ltd. launched a new concept in the UK and have since trained over one-quarter of all practicing UK dentists. This novel stent and application technique, which uses the preferred and superior paste resin composite, has now become commonplace and is the ideal solution for composite smile restorations using a matrix transfer.

After the digital design was trialled and agreed by the patient, the SmileFast stent was received with the chosen enamel shade of BL-XL IPS Empress Direct nano-hybrid paste composite from Ivoclar. The key features of this stent, which improves upon all existing techniques, are that it has 0.038mm metal separators built within the stent itself. This means that when the stent is loaded with composite resin and is placed, the separators slide between the teeth and fully-separate them from each other. This prevents the composite from sticking together between the teeth and allows for up to 10 teeth to be fully restored in only one application. Additionally, the stent is made from an inner clear silicone transfer medium encased within a hard acrylic carrier; this allows for excellent dimensional stability and extremely accurate transfer of shape and texture from the digital wax-up to the natural teeth.

Figure 15: Actual-size and over-sized 3D printed working models

Figure 16: External stains for characterisation

Figure 17: Showing the graduated translucency through the zirconia crowns

Figure 18: Exceptional tissue health after temporary crown removal

Figure 19: Direct comparison of the temporary versus the final restorations

The SmileFast stent ensures absolute dimensional stability and complete confidence when restoring multiple teeth, allowing the perfect transfer of the tooth shapes and sizes of the composite restorations onto the natural teeth (Fig. 5). On the day of placement, the stent was tried onto the patient’s teeth to ensure accurate fitting before the teeth were isolated by placing a hydrophobic barrier of PTFE tape down into the sulci of every tooth. This acts as a barrier to both prevent gingival crevicular fluid contaminating the bonding zone, as well as preventing composite from traveling into the sulcus during the composite placement. The teeth where microetched using an air abrasion unit with 50µ aluminium oxide powder to remove biofilm and increase micro-mechanical retention, followed by acid etching and bonding protocol. As there was a significant amount of exposed dentine, a selective etch technique utilising a 7th generation bonding system was used. This does not place a separate etch on the dentine first and utilises the short-acting and mild acidic component of the self-etching adhesive on the exposed dentine during the priming stage, which creates a thin hybrid-layer. This is less prone to hydrolysis than using a total-etch technique. Additionally, a more stable and durable bonding interface is created as there is only partial demineralisation of the dentine and consequent bonding to the hydroxyapatite crystal that remains[6,7].

Once tried in, the SmileFast stent was pre-loaded with heated paste composite and then placed on a heater to heat the entire stent to 140oF (60oC). Heating composite to this temperature is well-researched and shown to significantly improve the mechanical qualities of the material due to higher levels of monomer conversion when curing[8,9,10]. Using heated nano-hybrid paste composite guarantees better strength and wear resistance, which means that the SmileFast restorations will be more durable, less prone to failure and maintain their lustre for far longer than using the inferior flowable composite resin techniques[11]. Heating the material decreases the viscosity which then allows it to flow under pressure when the stent is applied to the teeth. The excess material comes out of the palatal-incisal evacuation vents. The scalloped stent design allows the clinician to remove any excess composite that extrudes gingivally before the restorations are cured through the stent.

On removal of the stent the exact replication of the 3D virtual wax-up is perfectly transferred onto the teeth (Fig. 6). The teeth are assessed for any voids or repairs, before a glycerine gel, or similar, is placed to seal the composite and they are given a final cure. Sealing composite is essential as the outer layer of resin is inhibited from fully curing due to the surrounding oxygen[11,12]. This leaves a sticky resinous layer on the outside of all freshly cured composite known as the Oxygen Inhibited Layer (OIL). If this OIL is not considered and removed before polishing begins, then one will find that composite will gather extrinsic stain very quickly and will lose its lustre also.

The full restoration of all the patient’s upper and lower teeth was completed using this process at the same visit in only 2 hours. We were able to immediately then place upper and lower orthodontic brackets using an in-direct set-up technique through CFast orthodontics. This stent-guided application method means a much quicker and simpler fixation of the bracket to the teeth. Due to the incredible accuracy of the SmileFast stent, the composite restorations placed are a perfect replication of the digital model on which the orthodontic set-up was manufactured, therefore the stent for the orthodontics was a perfect fit, as shown in Figure 7. Within 4 hours all the patient’s teeth were fully restored and the fixed orthodontics applied and activated with 0.014 NiTi wires (Fig. 8). After 5-months the teeth were aligned into a more favourable position and the passive over-eruption of the teeth had been reversed (Fig.9). The patient was comfortable and occlusion functioning well, so it was decided to move forward with the second phase of her rehabilitation, the planning and provision of her final ceramics.

Figure 20: Surface treatment for the zirconia restorations

Figure 21: Isolation for crown luting

Figure 22: Crown placement with cement excess

Figure 23: Simple removal of excess cement after tack curing

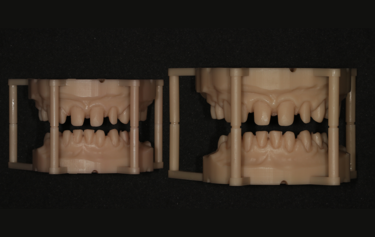

Digital scans were sent to the laboratory via 3Shape Trios intraoral scanner along with photos and instructions for the planned smile aesthetics. The scans were then imported into Exocad CAD design software and an upper and lower diagnostic digital mock-up was produced to create the best “first draft” of the expected outcome. The models were printed, and silicone indexes of the models made so that the diagnostic design could be transferred accurately to the mouth.

Given the patient’s reduced dental arch, high strength of the final restorations would be an essential property to support the mechanics of her masticatory function. Ivoclar IPS e.max ZirCAD Prime Esthetic was chosen as the restorative material as it has a considerably higher compressive strength over IPS e.max. In addition, the shade graduation technology gives the restorations more translucency toward the incisal edges and allows them to achieve the necessary natural colouring of real teeth that’s’ so vital in an aesthetic rehabilitation[13]. Bone-sounding was completed, and there was ample sulcus depth to allow removal of approximately 1-1.5mm from the unattached gingiva, still leaving approximately 2mm sulcus depth. Using a digitally printed guide based on the provisional digital mock-up, a diode-laser was used to gentle re-contour the gingiva to give better symmetry for the planned final restorations (Fig. 10). The teeth were then prepared to respect the minimum manufacture tolerance of Zirconia restorations, whilst keeping the preparation into the natural teeth as minimal as possible following the Gürel reduction technique[14]. This technique helps safeguard that only the necessary tooth-surface is sacrificed during crown or veneer preparation, and ensures that the correct thickness of reduction for the planned restorative medium is achieved. Depth grooves of 0.8mm were cut mid-facially and 1.5mm reductions incisally, and the teeth then prepared for full coverage restorations respecting these grooves as the maximum tooth reduction level (Fig. 11).

The initial preparations (Fig. 12) were scanned and then temporised with bis-acryl temporary medium. This trial smile was assessed by the patient for a few weeks so that they were able to get used to the new OVD, slight modifications to tooth size and shape, and for them to assess the aesthetics and phonetics. During this time, the scans of the now prepared upper and lower arches were converted via the Exocad software so that milled temporary crowns could be manufactured using Ivoclar Telio CAD in shade B1. On the 2-week review visit the interim temporary restorations were removed and the newly-made milled restorations placed. The function was assessed, and slight occlusal adjustment made until the bite was balanced. The temporaries were then scanned again so the laboratory was aware of the slight modifications to the shape occlusally.

A 6-week period was allowed to pass to give the gingiva time to heal and settle around the milled temporary restorations. On review the patient was very happy with the aesthetics of her smile but wanted the teeth a little whiter in colour. The form and function of the teeth was balanced, and the patient was comfortable at the new OVD. The temporary restorations were easily removed, followed by final refinement of the tooth preparations, and then retraction with PTFE placed into the sulcus ahead of a Trios intra-oral digital scan of the final preparations (Fig. 13). The posterior bite relationship of the prepared teeth was digitally recorded over the premolar area by using the anterior upper and lower 4 crowns to support the patient in the correct centric relation position.

Figure 24: Frontal retracted view – after

Figure 25: Full smile – after

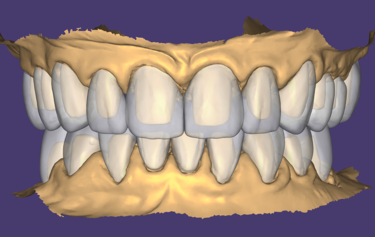

Figure 26: Direct comparison of the digital design versus the final restorations

On receiving the scans of the final tooth preparations, the laboratory was able to overlay the planned final restorations which the milled temporaries had been based upon. The small modifications to the occlusion which was completed at the earlier temporary stage could be adapted into the digital design, and then the individual restorations adapted to the refined finishing margins of the final tooth preparations (Fig. 14). The final restorations were then milled in IPS e.max ZirCAD Prime Esthetic in the lighter BL4 shade using the PrograMill PM7 milling unit. New working models were 3D-printed of the preparations, and a second set of oversized models were made to compensate for the increased size of the pre-sintered Zirconia (Fig.15). The larger model was scaled up to match the shrinkage factor of the zirconia to allow the restorations to be checked on the oversized model. This additional check stage allows for assessment of marginal fit and contact areas, in addition to checking the passivity of fit and the occlusion, ahead of sintering.

Some subtle surface shade modifications were then completed using a pre-sintering infiltration technique and IPS e.max zirconia colouring liquids (Fig. 16). Some B1 dentine shade was used in the cervical third to increase the chroma, and some blue and grey was used towards the incisal third to increase the appearance of translucency. A little orange shade was also used in the occlusal area of the posterior teeth. The restorations were dried in line with manufacturer recommendations, and they were then sintered in the Ivoclar S1 1600 furnace. After sintering the crowns were checked on the regular-sized working model, and because all these checks had already been made pre-sintering then there were no adjustments necessary. Additional surface texture was added and then the restorations were polished using rubber polishers. Some final characterisation was added using IPS Ivocolor and glazed with IPS Glaze Fluorescence. The final restorations have the perfect balance of individual character and depth of colour to mask the underlying tooth preparation, as well as the graduation of translucency to replicate that of natural teeth (Fig. 17).

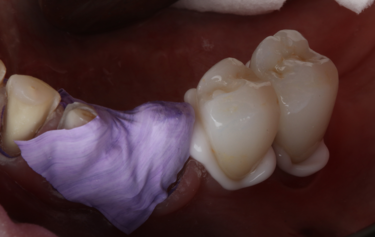

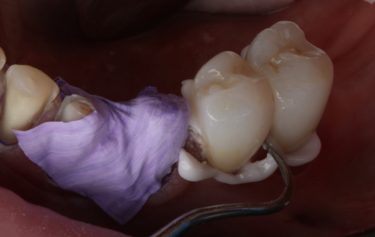

On the day of cementation, the temporary milled restorations were once again removed, and the exquisite gingival health observed (Fig. 18). By using the milled Telio-CAD temporaries the patient has far better control over their oral health around the restorations and the gingival health is always far superior to that when using a conventional ‘shrink-wrap’ technique. The new restorations were tried onto the teeth and the fit and aesthetics assessed. Figure 19 shows the exact replication of shape and size between the temporary (bottom) and final (top) restorations at this try-in stage. The teeth were prepared for bonding following standard protocol of air-abrasion to remove any biofilm and to create enhanced micromechanical retention, followed by a 2% chlorhexidine scrub.

The zirconia surface of the restorations was treated following the initial steps of the APC zirconia-bonding concept introduced and illustrated by Blatz et al. (2016)[15]. This protocol includes three steps: (A) air particle abrasion, (P) zirconia primer, and (C) adhesive composite resin. An abundance of research confirms the strong evidence that air-abrasion at a moderate pressure in combination with using phosphate monomer containing primers and luting resins provide long-term durable bonding to glass-infiltrated alumina and zirconia ceramic under the humid and stressful oral conditions[16,17]. In this situation, however, it was decided to lute the crowns rather than use an adhesive resin cement system. Adhesive bonds are ideally prepared to enamel, and as this was an existing TSL scenario, there had already been extensive enamel loss through erosion and attrition, exposing a significant amount of tooth dentine. With the preparation design for full crown restorations, the excellent retention form achieved through the long parallel-sided preparation designs, meant that this type of preparation is idealised for luting. As such, Ivoclar resin-modified glass ionomer cement, ZirCAD Cement, was chosen.

The restorations were placed into putty to protect the outer surface whilst the fitting surface was sandblasted. Due to the high attraction of the zirconia to phosphate molecules, contamination from local sources can bond to the zirconia surface and render it inert. Saliva and other body fluids contain various forms of phosphate, e.g. phospholipids, for example, and these may react more or less irreversibly with the surface. To optimise adhesion, scrubbing with Ivoclar Ivoclean removes any remaining phosphate contamination after sandblasting. Ivoclean consists of an alkaline suspension of zirconium oxide particles and due to the size and concentration of these, phosphate contaminants are much more likely to bond to them rather than to the surface of the zirconia restoration[18]. Ivoclean, when scrubbed over the zirconia fitting surface, will remove the phosphate molecules allowing a surface primed for optimum luting or bonding (Fig. 20).

Figures 21 to 23 show the steps when using the Ivoclar ZirCAD Cement. This was chosen due to it’s ease of application, self-cure chemistry, high fluoride release and efficient marginal clean-up via the tack-cure ability. Once the crowns were loaded and placed onto the teeth a 1-second tack-cure with a polymerisation light initiates an immediate semi-set of the excess cement at the margins. This then allows incredibly simple marginal clean-up using a sickle scaler followed by an ultrasonic scaler.

The patient returned after two weeks, and the final restorations were once again assessed. All margins, occlusion and excursions were re-checked and there were no further adjustments necessary (Fig. 24 & 25). Note the beautiful tooth morphology and the detailed surface texture that is achievable with modern digitally designed tooth libraries and state-of-the-art milling machines. The transfer of digital design to final restoration is an exact replication and this can be seen on the comparison of digital overlay against the final zirconia restorations in Figure 26

Figure 27: integration of final restorations at 2-week review versus initial presentation

Achieving perfect and natural smile aesthetics with ceramics is an incredibly time-consuming and high-skill procedure; however, now with the SmileFast system, digital workflow and highly aesthetic millable materials such as IPS e.max ZirCAD Prime Esthetic, the guided delivery of restorations supports dentists to feel more confident in offering this type of treatment modality to their patients. Providing patients a planning pathway that shows them all of the options and allows them to explore different routes to achieve a better smile is incredibly important, not only to build trust, but also to ensure better consent so that what they ultimately decide on is based upon a more informed and considered understanding of the techniques, risks and expected results.

By following a fully digital protocol we have been able to deliver to the patient exactly what she had agreed upon and predictably transfer the digitally planned restorations into her mouth in both restorative mediums of composite, and then ceramic. The digital workflow allowed for continuity through each stage, and the design of the temporary restorations once trialled and verified, could then be replicated in the final restorations. At every stage the patient knew exactly what they were getting in terms of occlusion, tooth shape and size. This protocol removes any chance of unwanted alteration in these areas that could be made when using a layering technique for example. This predictability not only reduces the stress and workload for the dentist, but also reduces the number of appointments necessary for the patient. Although the entire treatment and rehabilitation took almost a year, the number of appointments were minimised by this streamlined approach.

By approaching multiple restorations in the same methodical and planned approach every time, the SmileFast protocol, integrated with a digital ceramic workflow, guarantees predictable and consistently excellent aesthetic results. Figure 6 and 26 show the restored upper arch with composite (Fig. 6) and ceramics (Fig. 26) in direct comparison to the planned digital design; the accuracy of transfer is very precise, with the natural texture and the detailed morphology being replicated exactly.

Traditionally, zirconia restorations have lacked life-like character and have appeared too opaque or absent of the subtle details of natural teeth. Using the new ZirCAD Prime Esthetic, which is a combination of 4y-tzp and 5y-tzp zirconia, with the revolutionary integrated gradient technology, this material remains highly aesthetic yet retains the strength and functional properties that are synonymous with zirconia restorations. With the subtle external staining applied by a skilled ceramist, the final aesthetics are incredibly life-like with light absorption and reflective properties much closer to natural teeth than any other restorative materials in it’s class (Fig. 27).

This patient’s smile is now better balanced, with whiter teeth and more symmetry to the shapes (Fig. 25). The final restorations will require twice yearly review to monitor and assess occlusal stability and function. Over time the posterior support will be re-addressed, and implants again considered.

[1] Van't Spijker A , Rodriguez JM, Kreulen CM, Bronkhorst EM, Bartlett DW, Creugers NHJ (2009) Prevalence of tooth wear in adults. International Journal of prosthodontics; 22(1):35-42.

[2] Ray D S, Wiemann A H, Patel P B, Ding X, Kryscio R J, Miller C S. (2015) Estimation of the rate of tooth wear in permanent incisors: a cross-sectional digital radiographic study. J Oral Rehabil; 42:460-466.

[3] Bartlett D, O'Toole S. (2021) Tooth Wear: Best Evidence Consensus Statement. J Prosthodont; DOI: 10.1111/jopr.13312.

[4] Bartlett D W, Lussi A, West N X, Bouchard P, Sanz M, Bourgeois D. (2013) Prevalence of tooth wear on buccal and lingual surfaces and possible risk factors in young European adults. J Dent; 41: 1007-1013.

[5] Awad M A, El Kassas D, Al Harthi L et al. (2019) Prevalence, severity and explanatory factors of tooth wear in Arab populations. J Dent; 80: 69-74.

[6] Van Meerbeek B, Yoshihara K, Yoshida Y, Mine A, De Munck J, Van Landuyt KL (2011) State of the art of self-etch adhesives. Dental Materials; 27(1): 17-28.

[7] Van Landuyt KL, Yoshida Y, Hirata I, Snauwaert J, De Munck J, Okazaki M et al. (2008) Influence of the chemical structure of functional monomers on their adhesive performance. Journal of Restorative Dentistry; 87(8): 757-61.

[8] Daronch M, Rueggeberg F, Fernando de Goes F (2005) Monomer Conversion of Pre-heated Composite. Journal of Dental Research 84(7):663-667.

[9] Wagner WC et al. (2008) Effect of pre-heating resin composite on restoration microleakage. Operative Dentistry;33(1):72-8

[10] Calheiros FC, et al. (2014) Effect of temperature on composite polymerization stress and degree of conversion. Dental Materials 30(6):613-8.

[11] Vajani D, Tejani T H, Milosevic A (2020) Direct Composite Resin for the Management of Tooth Wear: A Systematic Review. Clinical Cosmetic Investigational Dentistry; 12: 465–475.

[12] Ruyter IE (1981). Unpolymerized surface layers on sealants. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 39(1):27-32.

[13] IPS e.max® Scientific report: Volume 3. 2001–2017 [Available at: http://www.ivoclarvivadent.com/zoolu-website/media/document/12839/IPS+e-max+Scientific+Report+Vol-+03+-+2001-2017.] Accessed 09/12/2023.

[14] Gürel G (2003). The Science and Art of Porcelain Laminate Veneers. Chicago, Illinois, USA: Quintessence Publishing.

[15] Blatz MB, Alvarez M, Sawyer K, Brindis M (2016) How to Bond Zirconia: The APC Concept. Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry; 37(9): 611-617.

[16] Kern M (2015) Bonding to oxide ceramics—laboratory testing versus clinical outcome. Dental Materials; 31(1):8-14.

[17] Mehta D, Shetty R (2010) Bonding to Zirconia: elucidating the confusion. International Dentistry South Africa; 12(2): 46-53.

[18] Wolfart M, Lehmann F, Wolfart S, Kern M (2007) Durability of the resin bond strength to zirconia ceramic after using different surface conditioning methods; Dental Materials; 23: 45.