Restoring Part of What Was Taken From Him

Originally published in Inside Dental Technology, April 2022.

As Lulu Tang, DMD, and her team at Sahara Modern Dentistry prepared the office for an annual "Serve Day" last year, they noticed an act of kindness occurring in their parking lot: A man who appeared to be homeless was helping a woman change her tire. Tang smiled to herself, but she had no idea at the time who the man was or the impact she would eventually have on his life—and he on hers.

Eric Proctor and a friend were wrongfully convicted of robbery and murder in 1986. The short version of the story is they were in the wrong place at the wrong time, and a crime laboratory analyst mistakenly identified debris on Proctor's clothing as gunpowder. After further testing revealed that mistake—and several others—from the investigation, and the real killer was caught on tape confessing, Proctor and his friend were released in 1994, and the charges were dismissed in 1995.1

Reassimilation into society was challenging, however. The nonprofit organization After Innocence notes on its website that, "Nearly all exonerees struggle for years and decades" because after their release they are "traumatized, broke, and usually without job skills or housing." Even two decades later, Proctor needed help, and one area of need was his failing dentition, which was attributed in part to the poor oral care provided in prison.

After Innocence set him up with an initial diagnostic visit and then sent him to Tang's office in Las Vegas, Nevada, for Serve Day, which she holds in conjunction with her business partner Pacific Dental Services (PDS). Tang was eager to help Proctor, but her enthusiasm was tempered: The preliminary treatment plan called for scaling and root planning and a few crowns in the mandible, but a full-arch extraction and immediate denture on the maxilla.

"I immediately thought that was impossible because I could only provide what could be done in my office," Tang says. "I did not believe any laboratory would ever donate a denture."

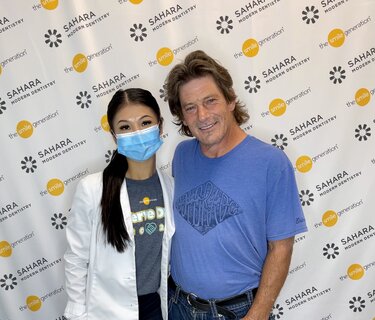

When Tang opened her doors on Serve Day, she was shocked to see the man who had changed the tire in the parking lot walk in and introduce himself as Eric Proctor.

"It was amazing to know his story of being wrongfully incarcerated, and then to see him changing a random person's tire in our parking lot?" Tang says. "As we spoke more that morning, I became compelled to change my perspective to, ‘I will figure out how to provide your treatment. Somehow, I will get you an immediate denture.'"

Tang finished the rest of Proctor's treatment that day and took alginate impressions of his maxillary arch. She then contacted a member of the PDS marketing team to see if the Ivoclar Group would be interested in donating some of its new milled denture material, Ivotion. The Ivoclar Group connected her to MicroDental Laboratories, which was already a preferred laboratory of PDS, and she spoke to MicroDental Director of Advanced Dentures and Implants Robert Kreyer, CDT.

At that point, Tang still thought the process could be difficult. Proctor lived in Arizona, several hours from her office. All she had at that point were stone models from the impressions. Kreyer asked her, however, to just scan the models and send them over for him to design the prosthetic.

"I was really surprised," Tang says. "That was my first exposure to a digital denture. It was amazing because I got to see the entire digital workup before he finalized it. The steps that required the patient to come to the office were eliminated."

Kreyer never met Proctor in person, but he learned about his story and studied photographs of him.

"Getting to know the patient is part of understanding their desires and expectations," Kreyer says. "Especially with complete prosthetics, so much psychology is involved. This patient was transitioning to complete dentures for the first time. As you work on the design, that goes through your mind: How will this affect the patient's life? We are all here for the patient. The ability to change somebody's life is why we do what we do."

Delivering the denture, Tang says, was particularly rewarding.

Tang herself grew up in a low-income household and knows the realities of problems with access to care. She underwent her own smile transformation at one point.

"For me, it was not just the physical smile, but also the confidence and self-esteem," she says. "Just observing Eric talking and laughing, I knew we were giving him that confidence. Dental work can seem so unattainable to so many people, so being able to not only provide this level of care to someone but also to collaborate with a laboratory and a manufacturer on it was something incredible that I never thought possible. That took it to another level. Knowing now that I am not limited by what I can do in my own office makes me more excited for our next Serve Day."

Kreyer echoed her sentiments about the collaborative element of this case.

"We all collaborated together to provide the materials, the design, and the expertise on both the technical and clinical side," Kreyer says. "Working on this case was very gratifying, and even more so because of the patient. I am really happy that I was able to contribute a small part to make a difference in his life, and I hope stories like this inspire more people to help others who are in need."

Reference

1. Eric Proctor. The National Registry of Exonerations website. law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/casedetail.aspx?caseid=3552. Updated September 13, 2019. Accessed February 11, 2022.

Receive our monthly newsletter on recently published blog articles, upcoming education programs and exciting new product campaigns!